Ever since he was chosen as Donald Trump’s running mate back in July, U.S. Sen. JD Vance, a Republican from Ohio, has come under a level of scrutiny typical for a vice presidential candidate, including for some of his eyebrow-raising public statements made in the past or during the campaign.

One line of critique has persisted through the news cycles: that his lack of political experience may make Vance less qualified than others, including his opponent, Gov. Tim Walz of Minnesota, to be vice president.

Do more politically experienced politicians have advantages in elections? And if they enjoyed such advantages in the past, do they still in such a polarized political moment?

The answers are complicated, but political science offers some clues.

Why experience should matter

Previously holding political office, and for a longer period of time, is in some ways an obvious advantage for candidates making the case to potential voters. If you were applying for a job as an attorney, previous legal experience would be favorably looked upon by an employer. The same is true in elections: If you want to run for office, experience as an officeholder could help you perform better at the job you’re asking for.

This approach has been taken by a number of high-profile politicians over the years. For example, in Hillary Clinton’s first campaign for president in 2008, the U.S. senator from New York and future secretary of state made “strength and experience” the centerpiece of her argument to the voters.

Experience also might matter for the same reasons as incumbency – that is, when a candidate is currently holding the office they are seeking in an election. Incumbents typically have much higher name recognition than their challenger opponents, distinct fundraising advantages and, at least in theory, a record of policy achievement on which to base their campaigns. Even for nonincumbents, these advantages are more prevalent for previous officeholders rather than someone who is a newcomer to politics.

Inexperienced, or an ‘outsider’?

But Hillary Clinton was, of course, unsuccessful in her first bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2008. She was beaten by a relatively inexperienced candidate named Barack Obama; like Vance, Obama had served less than a full term in the Senate before running for higher office.

Obama’s 2008 win shows that a lack of political experience can be leveraged as a benefit.

One of the few things Obama and Donald Trump have in common is that both benefited from an appeal to voters as a political “outsider” in elections in which Americans were frustrated with the political status quo. As outsiders, they appeared uniquely positioned to fix what voters believed was wrong with politics.

Does experience equal ‘quality’?

The “outsider” label isn’t always a ticket to victory.

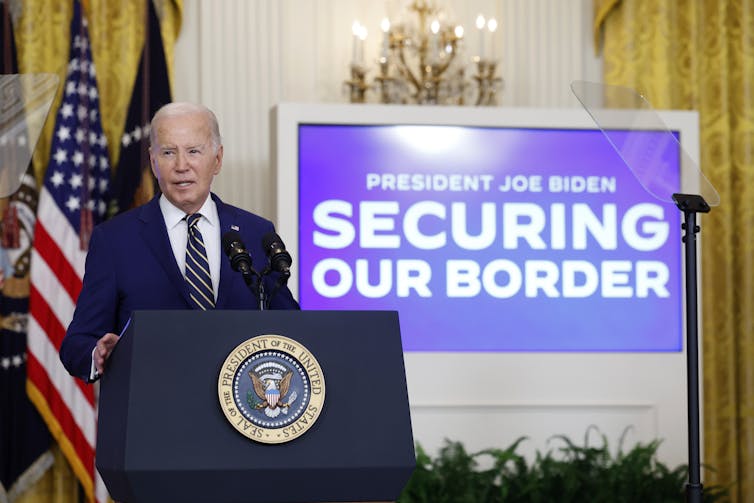

In 2020, for example, voters were frustrated with the chaos of having a political outsider in the White House and turned to Joe Biden – possibly the most experienced presidential candidate in modern history at that point, with eight years as vice president and several decades in the Senate under his belt. Voters were hungry for political normalcy in the White House and made that choice for Biden.

Political science has other important lessons about when experience matters and when it doesn’t. In Congress, electoral challengers – those running against incumbents – enjoy more of a boost from prior experience in places such as the state legislature. In fact, the typical indicator for challenger “quality” used in political science research is a simple marker of whether the challenger has prior political experience.

But even this finding is more complicated than it seems: Political scientists such as Jeffrey Lazarus have found that high-quality – that is, politically experienced – challengers do better in part because they are more strategic in waiting for better opportunities to run in winnable races.

Experience matters only sometimes – and maybe less than ever

The usefulness of a lengthy political resume also depends on which stage of the election candidates are in.

Research has found, for example, that a candidate’s experience matters much more in settings such as party primaries, where differences between the candidates on policy issues are typically much narrower. That leaves nonpolicy differences such as experience to play a bigger role.

In the general election, voters supportive of one party are unlikely to factor candidate experience in that heavily, even, or especially, when the candidate they support lacks it.

The political science phenomenon known as negative partisanship means that, more and more, voters are motivated not by positive attributes of their own party’s candidates but rather by the fear of losing to the other side. This has only been exacerbated as the two parties have polarized further.

Voters are therefore more willing than ever to lower the standards they might have for their favored candidates’ resumes if it means beating the other side. Even if a Democrat is clearly more qualified than a Republican in terms of political experience, that advantage is unlikely to sway many Republican voters, and vice versa.

What about 2024?

In 2024, the experience factor is complicated. Trump, of course, has been president before – the ultimate prior experience for someone running for exactly that office.

But he has continued to run as an outsider from the political establishment, casting Kamala Harris – who, as vice president, has little actual institutional power – as an incumbent who is responsible for the current state of the country. Since polls show consistently that a majority of Americans believe the country is not headed in the right direction, we can see why Trump might try to frame the race in this way.

Whether Trump’s strategy ends up working will be more apparent after the election is over. For now, Trump and Harris can rest assured that most of their supporters don’t appear to care how much – or how little – experience they have.

Charlie Hunt, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Boise State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.